For many, it seems hardly noteworthy to mention that the world is ageing. Contrary to common belief, it’s not only European and high-income countries that are ageing. Many middle and low-income countries like Tanzania are also experiencing impressive growth rates of their older populations [1].

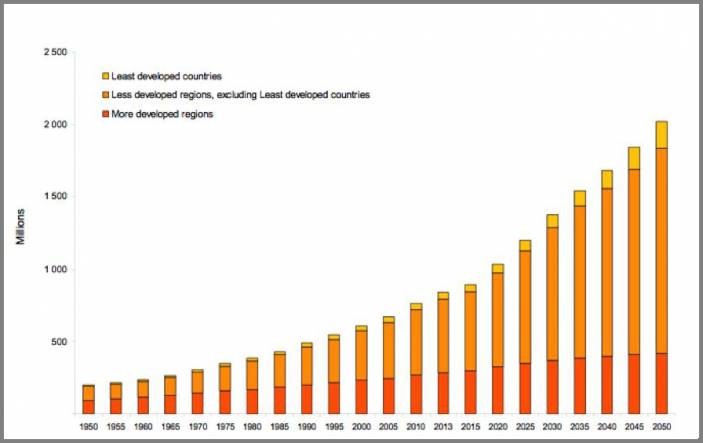

Figure 1: Population aged 60 years by development region, 1950-2050 (UN DESA 2013)

Figure 1: Population aged 60 years by development region, 1950-2050 (UN DESA 2013)

According to HelpAge’s 2014 Global AgeWatch Index[2], Tanzania ranks 92 out of 96 countries regarding the wellbeing of older people.

This poses questions from a health perspective, as who will care for an increasingly older and poor population when the health system in Tanzania is underfunded and lacks resources?[3]

Impact of ageing populations on healthcare issues

This question is even more urgent as Tanzania not only faces a demographic transition but also an epidemiologic transition from communicable diseases like malaria to non-communicable and chronic conditions (NCDs) like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, mental health issues and cancers.

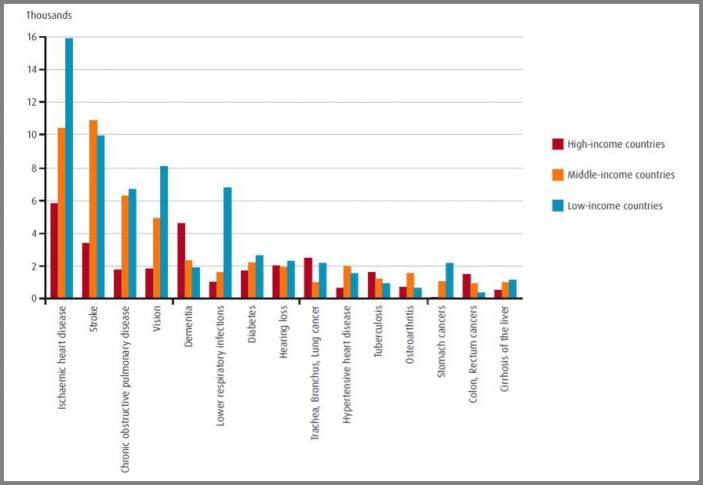

Contrary to the myth surrounding NCDs, it is not high-income countries that suffer most, but low- and middle-income countries with the more vulnerable elderly population especially at risk (see fig.2). These chronic conditions often require long and costly care and constitute an enormous care burden. But who cares? Figure 2: Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) per 100,000 adults over age 60 by country income group (WHO 2012).[4]

Figure 2: Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) per 100,000 adults over age 60 by country income group (WHO 2012).[4]

In 2003, the government of Tanzania issued a National Ageing Policy.[5] With regard to care for older people, it states that the family should be the main provider. Yet the traditional extended family in rural Tanzania has been under immense pressure due to urbanisation, internal migration and the impact of HIV and AIDS. As a consequence, older people are part of fragmented extended families that usually fail to provide adequate care for them.

Faces behind the figures

What then are the care realities of older people in Tanzania’s rural small-scale farmer communities? Who are the faces behind the figures?

What then are the care realities of older people in Tanzania’s rural small-scale farmer communities? Who are the faces behind the figures?

Mzee[6] Ikonga[7] grew up in a remote village in rural Ulanga district, in the South of Tanzania. In his youth, he migrated to town to find work as a day labourer in the cotton industry. After ten years, he could no longer work as his eyesight had faded and he returned to his village. He was only in his mid-thirties.

Upon his return, he presented his eye problems at the local dispensary and was told to travel to a far away eye clinic for further diagnosis and, possibly, treatment. Yet he was unable to cover the costs of even the journey.

He then turned to a traditional healer who provided him with medicine. After a month, he was disillusioned with the ineffective treatment and didn’t return. He was left almost completely blind.

Some 20 years later, now 64 years old mzee Ikonga lives in a small brick hut with his wife and two of his granddaughters.

Financial means are limited in many rural communities

He is well cared for by his wife who feeds him, washes his clothes, helps him bathe and guides him to the dispensary. He is also fortunate to have all his six children living nearby, which ensures his survival. But he remains poor and can hardly expect any financial help from his children for even basic goods like soap, salt and sugar.

He explains: “I have not received any help from those children. It’s not easy for you to give me money while you yourself are in an equally bad situation.”

Some children and relatives manage to save a few shillings for older people. But the financial means to do so – income gained from selling eggs, chickens or some crops at the village market – are extremely limited.

This has repercussions for older people’s access to healthcare services. In the case of mzee Ikonga, it means he will have to remain blind. Guided by his wife, he continues working in their field even though he occasionally weeds the maize instead of the grass.

Governments must do more for older people

For families like his then, putting the family at the centre of care, as suggested by the National Ageing Policy of Tanzania, hardly seems promising. Mzee Ikonga urges the government to do more for older people.

“The government does not care about us, they just don’t care. (…) I have often heard it in the media that older people in Bagamoyo are saying that it is us who brought freedom to this country but the government does not care about us!

“Myself, I would really thank the government if it recognised me as an older man who needs help to have a decent house… I would appreciate it. We older people deserve to get some breakfast and a piece of soap.”

Find out more about HelpAge International’s work to support older people in Tanzania.

References:

[1] http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf

[2] http://www.helpage.org/global-agewatch/

[3] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23254848

[4] http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2012/WHO_DCO_WHD_2012.2_eng.pdf

[5] http://www.globalaging.org/elderrights/world/2007/BGTanzania.pdf

[6] Mzee is a title of respect in Kiswahili, usually used for older men.

[7] Name changed